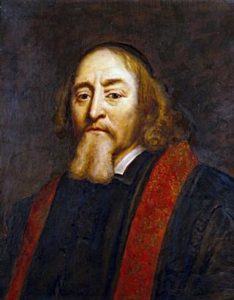

I feel deep empathy with Jan Ámos Komenský (1592 – 1670), known as Comenius, through his Utopian vision of a society based on Universal Wisdom, which he called Pansophia, from Greek pansophos ‘very wise’, literally ‘all-wise’, from pan ‘all’ and sophia ‘wisdom’.

Pansophia would be based on pansophy meaning ‘universal or cyclopædic knowledge; a scheme or cyclopædic work embracing the whole body of human knowledge’, which Frank E. and Fritzie P. Manuel called a ‘dream of science’ in their scholarly tome Utopian Thought in the Western World.

Our starting points for this vision of the unification of science, philosophy, and religion were similar. As an adolescent, I could see that what I was being taught in religion, science, and economics did not make sense as a coherent whole. So when I saw in the late 1970s that my children were also not being educated to live in the world they would be living in when they were bringing up children of their own, I set out to discover how they and I should have been educated.

As there were no teachers of what I began to call Panosophy in 2002—healing the fragmented, specialist mind in Wholeness—I became an autodidact in 1980 being guided solely by my inner guru, which the Greeks and Romans called daimon and genius, respectively.

Comenius, today known as the ‘father of modern education’, began his own endeavours to reform the education system of his day with a book titled The Great Didactic: Setting Forth the Whole Art of Teaching All Things to All Men, by which he meant women and well as men, girls as well as boys, engaged in a life of learning.

We can see from his spiritual classic The Labyrinth of the World and The Paradise of the Heart that Comenius was being guided in this great endeavour through his mystical union with the Divine, which he called Christian, knowing no other language through which to express his inner experiences. This meant that he went much deeper than Francis Bacon’s Great Renewal and his contemporary René Descartes’ dream of “the unification and the illumination of the whole of science, even the whole of knowledge, by one and the same method: the method of reason”.

![]()

To understand Comenius’s central importance to the completion of the final revolution in science that we are engaged in today, we need to look at the similarities of his times, when Kepler and Newton brought about the first scientific revolution, and our own. For revolutionary ways of looking at the world we all live in can only become established in society through groups of people coming together to embrace the new worldview and ideas and institutions that follow from it.

Comenius lived at the end of the Humanist Renaissance amid much religious conflict, when the universities were still stuck in the Middle Ages, following Aristotelianism, despite Bacon and Kepler, incapable of adapting themselves to the requirements of the new age, oblivious to the new ideas and experimental methods in science that were emerging at the time.

Most specifically, concerning the reform of centres of higher learning, in The Great Didactic, Comenius envisioned a school of schools or Universal College that “would bear the same relation to other schools that the belly bears to the other members of the body, that of a living laboratory supplying sap, vitality, and strength to all”.

This was essential, for, as he said, “Textbooks lacked harmony and co-ordination, having been written by ‘specialists’, that is, men who, outside of their particular specialty, knew next to nothing.” Comenius was thus much concerned with the problem of the fragmented mind, which David Bohm highlighted in 1980 in Wholeness and the Implicate Order. As Comenius, himself, wrote:

Metaphysicians sing to themselves alone, natural philosophers chant their own praises, astronomers dance by themselves, ethical thinkers make their laws for themselves, politicians lay their own foundations, mathematicians rejoice over their own triumphs, and theologians rule for their own benefit. Yea, men introduce even into the same field of knowledge and science contradictory principles whereby they build and defend whatever pleases them, without much troubling themselves about the conclusions derived from the premises by other men.

Accordingly, inspired by Bacon’s classification of all fields of learning and his New Organon, in which Bacon extended Aristotle’s deductive reasoning with the scientific method of induction, Comenius set out to explore how this problem of fragmentation could be solved, rewriting textbooks that fit together as a coherent whole, grounded on the depths of spiritual understanding, unifying science and religion.

I felt much the same challenge in 1980, when I set out to develop a cosmology of cosmologies that would unify the psychospiritual and physical energies at work in the Universe. I remember standing in Foyles bookshop in Charing Cross Road in London saying to myself that all the books on science, philosophy, and religion would need to rewritten.

This I set out to do, later taking advantage of the Internet as a repository of all the world’s knowledge, possible because the modelling methods underlying this network of networks are universal, applicable in all cultures, disciplines, and industries. As a generalist, I was then able to take the abstractions of pure mathematics to their utmost level of all-inclusiveness with Aristotle’s notion of being.

But what was Comenius to call this megasynthesis of all knowledge? Three hundred years later Pierre Teilhard de Chardin prophesied that the unification of science and religion would come about when all the divergent streams of evolution converged in Wholeness, the True Nature of all beings, recapitulating what Joseph Campbell was to call the Cosmogonic Cycle. In the event, Comenius, living far ahead of his time, found the word that he needed in a now forgotten book by Peter Laurenburg, published in 1633, titled Pansophia, sive Pædia Philosophica (Universal Wisdom, or A Philosophy of Education).

However, Comenius did not feel that this book lived up to its title and so he set out to write a work describing the fundamental principles of Christian Pansophia that did. He believed that men could be trained to see the underlying harmony of the Universe and thus to overcome its apparent disharmony, writing “pansophy propoundeth to itself so to expand and lay open to the eyes of all the wholeness of things that everything might be pleasurable in itself and necessary for the expanding of the appetite.”

![]()

In 1637, Comenius sent the first draft of his proposals to Samuel Hartlib, a German-English philanthropist and scientific enthusiast living in London, with whom he had been corresponding for five years. But rather than continuing their dialogue, Comenius was surprised to learn that Hartlib had published his sketch as Introduction to Panosphy, known as Prodomus, even getting the permission of the censor at Oxford University to do so. Hartlib, acting as publicity agent for the Moravian bishop, even suggested the establishment of a college based on Comenius’s plan, before the publication of The Great Didactic.

Now while Prodomus was generally received with hearty and enthusiastic acclaim, there were a number of detractors, who objected to the scheme on the grounds that it confounded philosophy with theology, as Descartes said, and “matters divine and human, theology with philosophy, Christianity with paganism, and thus darkness with light”, as a noble member of Comenius’s own congregation opined.

To answer these critics, emphasizing the spiritual or Christian dimension of this enterprise, in 1639, Comenius wrote Explanation of Pansophy. In 1642, “upon the request of many”, Hartlib then published an English translation of these two ‘excellent treatises’ with the title A Reformation of Schooles. That is how I came to discover the first use of pansophy in English in the Oxford English Dictionary in 2002, mentioning Hartlib, as the publisher, not Comenius, as the author. At the time, I had just coined panosophy modelled on philosophy,

There the matter might have rested, just debated in academic circles. However, there was so much longing to be free of old ways of thinking, not unlike today, that a movement was formed to put Comenius’s proposals into practice. In particular, Christians, fed up with the Thirty Years’ War, sought to reconcile their different interpretations of Christianity to find the Sameness that they all shared as human beings, Christian or otherwise. Foremost among these ecumenical advocates of church union was John Dury, one of Hartlib’s closest friends.

The great turning point in Comenius’s life came about as the result of a sermon that John Gauden, later to become a bishop in the Church of England, gave on 29th November 1640 before the House of Commons of the Long Parliament on the topic of ‘The Love of Truth and Peace’. In this sermon, Gauden urged that Comenius and Dury be invited to London. Although no official invitation was issued, a group of parliamentarians from both houses asked Hartlib in June 1641 to send Comenius an invitation to go to London to meet Dury and others to explore the development of their shared interests.

This invitation gave Comenius something of a dilemma. He was reluctant to leave his position as rector of his school in Poland, as a bishop in his church, and his family. However, Comenius, under the impression that the invitation was an official one from the British government, received permission from his colleagues to travel to London, across a stormy North Sea, on the understanding that he would soon return. Upon arrival in London in September 1641, Comenius was much disappointed that the invitation only came from a few of Hartlib’s associates, who urged Comenius to settle permanently in England.

For Comenius’s friends had given him the impression that Parliament would provide funding for research projects within a Pansophic College based in London. In the event, this came to nothing, for the English Civil war broke out on 22nd August 1642. So any hope that the necessary state support would eventually be forthcoming was abandoned.

![]()

Nevertheless, Comenius did have the opportunity to meet several leading thinkers of the day while in London and to write a new tract on his educational vision titled Via Lucis (The Way of Light), translated into English in 1938, a copy of which I have so far been unable to obtain. Although this “ill-drawn and discursive treatise” was written under difficult conditions, Matthew Spinka tells us in his biography of Comenius, an ‘Incomparable Moravian’, that five points stand out:

- Universal textbooks should be used everywhere to train scholars for an intelligent, purposeful life rather than merely cramming their heads with uncoordinated bits of knowledge.

- These universal textbooks should be based on the idea that nothing is known unless it is known in its development.

- As a corollary, the plan included a digest of past learning, drawing out the quintessence of what authors have previously decided and agreed upon. “A few men must undertake the task of swallowing and digesting all that troublesome mass of writings once and for all, so that all other men may be relieved and set free from it for ever.”

- In contrast, Comenius was not satisfied with the status quo and keenly felt the need for a fresh, creative approach to education, coordinated in a central research institution: the Pansophic College.

- The scope of the education system should be international, transcending national boundaries.

As Spinka commented in 1943, “Were the grandiose project accomplished in our day, what a boon it would be! But alas! the world is still waiting for its realization, and we seem to be further away from it than ever.” But is there still a chance that such a centre of Universal Wisdom and Light could be established in the Age of Light before the extinction of our species? Like today, Comenius saw his times as the eventide of the world, quoting Zachariah, “And it shall come to pass that at eventide there shall be light.”

![]()

It is an enormous challenge, as we can see from what happened to Comenius’s vision after he left London in 1642. Theodore Haak, who was a close friend of Hartlib and was one of the co-workers on the pansophic scheme in 1641, arranged meetings from 1645 of a few “worthy persons inquisitive into Natural Philosophy”, forming a club known as the ‘Invisible College’. This association of natural philosophers promoting knowledge of the so-called natural world through observation and experiment was the precursor to the Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, established with this title in 1663, as its website tells us.

However, in 1967, Margery Purver published a book titled The Royal Society: Concept and Creation disputing the Royal Society’s own history of its foundation. By studying many original documents, she argued that the Royal Society did not evolve from Comenius’ proposal for an Academy of Universal Wisdom and Light. She said that the evidence indicates that the Royal Society evolved from the Oxford Experimental Science Club founded by John Wilkins about 1648, then Warden of Wadham College, moving to London in 1660, nothing do with ‘Pansophia’. So although Francis Bacon inspired both the Pansophic College and the Royal Society, Hugh Trevor-Roper wrote in his introduction to The Royal Society that the Hartlib-Comenius mystical expansion of Bacon’s proposals was nothing more than a ‘vulgarization’, nothing to do with scientific method.

This is not how Comenius saw the foundation of the Royal Society. When The Way of Light was eventually published in 1668, Comenius, in his innocence, thought that this learned society in England was a development of his pansophic vision. As he wrote in his dedicatory letter to the Society, “Blessings upon your heroic enterprises, illustrious Sirs! We have no envy towards you; rather we congratulate you and assure you of the applause of mankind,” taking a somewhat proprietary tone.

Yet, as Einstein wrote in 1946, if we are ever to find the root cause of conflict and suffering in order that we might live in love, peace, and harmony with each other, we need to make a fundamental change to scientific method, engaging in introspection.

Comenius outlined such a reformation of the way we learn about the world we live in, including ourselves, in Panaugia ‘Universal Light’, written a couple of years after leaving London. As he said, we have three eyes through which to learn wisdom: the five senses, reason and intelligence, and meditation on or contemplation of the Divine.

Ken Wilber said much the same thing in Eye to Eye in 1983 with his three eyes of flesh, reason, and contemplation. Similarly, Franklin Merrell-Wolff wrote in Transformations in Consciousness, posthumously edited by his grandson-in-law Ron Leonard in 1997, there are three primary functional forms of consciousness: perception, conception, and introception. And more recently, Bernardo Kastrup wrote in his afterword to Rupert Spira’s The Nature of Consciousness in 2017, “we can acquire knowledge through three distinct avenues: empirical observation, rational thought and introspection.”

It is thus time to redress this imbalance in scientific method, putting into practice the Royal Society’s motto, which is Nullius in verba, which roughly translates as ‘take nobody’s word for it.’ As the Royal Society’s website says, this motto “is an expression of the determination of Fellows to withstand the domination of authority and to verify all statements by an appeal to facts determined by experiment.” And its mission is: “To recognise, promote, and support excellence in science and to encourage the development and use of science for the benefit of humanity.”

However, progress is still slow. For instance, Uta Frith, emeritus professor at the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, pointed out that the scientific establishment is very far from accepting psychology in any form as a valid science. In an interview in The Guardian on 30th November 2015 under the rubric ‘Where next for the Royal Society?’ to mark Venki Ramakrishnan taking over as the President of the Royal Society, she said,

My own field, call it psychology, or cognitive or behavioural neuroscience, still leads a rather shadowy existence in the hallowed halls of science. Although nearly 100 years old, it is far from maturity. There is as yet no Newton. Many would agree that one of the biggest scientific challenges this century is to understand the mind-brain. So I dare hope that it will be possible to increase the number of outstanding scientists in this field, currently representing less than three per cent of the Fellowship.

This would lead to an increase in the prestige of mind-brain studies and attract more brilliant young researchers. One reason for the currently poor reputation of psychology is the obstinate belief that we already know what goes on in our mind, and that we can explain why we do what we do. This naïve belief will be overcome by improved communication of empirical findings, and especially of those that go against ingrained folk psychology. It’s not rocket science. It’s a lot harder than that.

![]()

For myself, I set out to invite people to join me in fulfilling Comenius’s vision in 1984, long before I had heard of this remarkable man or had thought of Panosophy as the transdisciplinary synthesis of all knowledge. Rather, on 29th October that year, I coined the word paragonian following several weeks searching Greek and Latin dictionaries in Wimbledon library in London. The word derives from the Greek words para ‘beyond’ and agon ‘contest’ or ‘conflict’, a word that is also the root of agony, until the 17th century meaning ‘mental stress’, antagonist ‘a person who one struggles against’, and protagonist ‘leading person in a contest’.

Paragonian thus means ‘beyond conflict and suffering’, a healthy, liberated, and awakened way of being that we can realize when we are both unified with the Divine and integrated with the Cosmos; when we base our lives firmly and squarely on Nonduality, on our Immortal Ground of Being. Paragonian thus denotes the essence of Advaita (‘not-two’) in a word with a Western etymology.

Then a couple of years later, I attempted to set up the Paragonian Institute with my Norwegian wife, which became the Paragonian Foundation in 2004, after we divorced after I rejoined IBM in Stockholm in 1990, taking early retirement in 1997. In 2004, when I moved to the west coast of Sweden, I also published my first book in the transdisciplinary genre of Panosophy, titled The Paragonian Manifesto: Revealing the Coherent Light of Consciousness. My social function as a Panosopher had evolved from my job as an information systems architect, developing a coherent model of all processes and entities in business.

Economically, this revolutionary book was my first public attempt to outline the holistic and spiritual principles of the Sharing Economy, just as Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations and The Communist Manifesto by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels had laid down the basic principles of capitalism and communism in 1776 and 1848, respectively.

However, it was not until 2014 that I felt moved to investigate the origins of the word pansophy, thereby discovering the life and work of Comenius, which I summarized in eight pages in my book The Theory of Everything in September that year, answering this advertisement in the New Scientist from April 2005.

However, it was not until 2014 that I felt moved to investigate the origins of the word pansophy, thereby discovering the life and work of Comenius, which I summarized in eight pages in my book The Theory of Everything in September that year, answering this advertisement in the New Scientist from April 2005.

Since then, I have written a couple more books explaining the root causes of the accelerating pace of change in society in the context of evolution as a whole, in both the vertical and horizontal dimensions of time, available on my website for the Alliance for Mystical Pragmatics, which I am still endeavouring to set up in order to complete the final revolution in science. But, first, as Comenius is not a well-known figure, let us spend a moment looking at how he coped with the challenges of his own times.

![]()

Comenius was born in Czech-speaking Moravia to devout members of Unitas Fratrum ‘Unity of Brethren’, originally inspired by John Wycliffe and Jan Hus’s attempts to reform the Catholic Church, a century before the Protestant Reformation of Martin Luther. The Unity of Brethren had been founded in 1457 by Petr Chelčický, an early prophet of absolute pacifism, regarding the use of force as un-Christian. Leo Tolstoy referenced Chelčický’s ‘marvellous book’ The Net of Faith in The Kingdom of God Is Within You as an example of non-resistance, Tolstoy’s book being an inspiration for Mohandas Gandhi’s policy of passive resistance to oppression.

Needless to say, in the decades leading up to the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1648), a group of Christians seeking to live in love and peace with each other had a rather tough time of it, to which were added some personal tragedies in Comenius’s life. When he was twelve, both his parents and two sisters died suddenly, possibly of the plague.

Comenius then went to live with an aunt, who sent him to school, a period of bitter hardship, being painfully subjected “to the crudities and consequent cruelties inherent in the current system of education”. This triggered his interest in reforming the education system, wishing to save future generations of pupils from the treatment he had received, not unlike me.

Things went better when he was sent to a Latin school at sixteen, where he was given the middle name Ámos because of his love of learning, a play on Latin amare ‘to love’. He had much support from his teachers, for Comenius saw his future as a priest, later graduating from the Universities of Hebron and Heidelberg. He was ordained at twenty-four and became a bishop or elder of the church at forty.

In his early twenties, when he also began his teaching career, Comenius also undertook the colossal task of writing, single-handed, a sixteen-volume encyclopaedia in Czech, comprising all things from the creation to his day, rather like me 350 years later. Not surprising, this overly ambitious project was never completed, some of which was lost in a disastrous fire in 1656.

While Comenius was seeking to establish his career, get married, and have children, all around him was much religious turmoil, as the Unity of Brethren faced much bullying and harassment from Catholics at his first parish in Fulnek, Comenius bearing such insults patiently, as a chronicler was later to report. However, at the beginning of the Thirty Years’ War, Fulnek was sacked and Comenius’s house was burned to the ground.

Comenius went into hiding, his wife returning to live with her mother, where she died of the plague, along with their two children. He became a fugitive in his own land, being ordered to leave by the Hapsburg authorities in 1628. Comenius moved to Leszno in Poland, becoming a wanderer for the rest of his life, as an exile and citizen of the world.

![]()

When Comenius was in hiding during the early 1620s, he wrote what is today regarded as a masterpiece of Czech literature. This book, revised twice in Comenius’s lifetime, was titled The Labyrinth of the World and The Paradise of the Heart, in two parts, as the title suggests.

The book was written as a satirical allegory of a pilgrim seeking Inner Peace “in these exceedingly turbulent and disturbing times”, as Comenius wrote in the opening words of the dedicatory letter to his protector and benefactor Count Žerotín. Nothing much has changed in nearly four hundred years, still much restricted in discovering the truth of life on Earth by Vanity and Delusion, as Comenius put it, two of the symptoms of what Erich Fromm was to call our sick society in the 1950s.

For me, this classic of psychospiritual literature, which has been likened to the works of Nicholas of Cusa, who much inspired Carl Gustav Jung in his explorations of the hidden depths of the psyche, provides me with a brilliant mirror for my own endeavours to disentangle the labyrinth of the world so that I can bring order to my fragmented, split mind in Wholeness. For in this healing manner, I have found the paradise of the heart in union with the Divine, just as Comenius described—so long as wishing to bring Comenius’s pansophic dream into the twenty-first century does not disturb me.

After moving to Leszlo, becoming co-rector of a school there, Comenius set out on his pedagogical mission to reform the education system, both in the classroom and in its infrastructure. Clearly blessed with much self-awareness of the dynamics of the learning process, during his first three years there he used his ‘leisure hours’ to write a textbook titled Janua linguarum reserata (The Gate of Languages Unlocked), which was a phenomenal success, being quickly translated into several European languages, as well as Arabic and Persian a little later.

This naturalistic textbook made him known throughout Europe, instantly establishing his fame and placing him among the chief educational reformers of his age. Comenius was utterly dissatisfied with the clumsy and unsuitable methods of teaching Latin, with pupils being taught words with no reference to the things they signified. Being aware that it is more natural to think in terms of pictures, as mental images, than words, as Einstein observed, Comenius sought to teach Latin in a way that pupils could relate to in their own direct experience, rather than through the Latin classics, which were too difficult for beginners.

In terms of the education system as a whole, Comenius based his thoughts on this on his profound understanding of human development from birth to death. In 1631, he began work on his Didactica magna, originally in Czech, expanded in Latin in 1636–37, but not published until 1657. In this book, Comenius proposed that the education system should be based on the needs of pupils, dividing the entire process into four periods of six years each.

During the first period, the ‘school of infancy’, the child would learn the mother-tongue, the use of the senses, and be trained in good habits, including Christian devotion. From seven to twelve, in ‘vernacular schools’, children, from all social backgrounds, would then learn the basic skills of reading, writing, and arithmetic, as well as singing and a modern foreign language. Those with the necessary ability would then attend ‘Latin schools’, learning not only the classical languages of the Bible, but also the natural sciences and useful arts, based on Baconian principles. Finally, the intellectual elite would attend a university to be established in every province or kingdom, preparing for some specialist profession, unified through a transdisciplinary Universal College.

Although Comenius was not the first to propose such a reformation of the education system, the authority of his reputation led it to become gradually accepted throughout Europe, leading to the establishment of Universal Education that we are familiar with today during the twentieth century.

![]()

As mentioned above, Comenius’s ideas on the transformation of the education system and the unification of the warring factions of Christianity led him to visit London in 1641, apparently of no avail at the time. Nevertheless, when Comenius left England, he found himself in great demand throughout Europe, even receiving an invitation from Cardinal Richelieu in France, and from the five-year-old Harvard University in the British colony, to become the USA.

While deciding what to do with the rest of his life, he met Descartes in the Netherlands for four hours, agreeing to disagree, Descartes saying in parting, “I will not go beyond the realm of philosophy; accordingly, I shall deal with only a part of that which you will treat in entirety.”

This was the year after Descartes had published his Meditations on the dualistic split between mind and matter, from which Western thought is still to recover. Similarly, in A History of Western Philosophy, Bertrand Russell denoted philosophy as lying between science and theology. But when we stand outside both East and West, science and theology, as the study of God, are unified in Panosophy and these divisions no longer exist.

Back in 1642, Comenius was being pulled in several directions at once. His friends in England and he, himself, wanted him to continue developing his pansophic vision. But he was also a family man, headmaster, and a bishop in the Unity of Brethren, seeking peace and harmony throughout Christendom, known as irenics, from Greek eirēnē ‘peace’.

In the event, as his church was severely short of funds, money spoke loudest. Comenius accepted an invitation from the chancellor of Sweden, Axel Oxenstierna, effectively the regent of Sweden until Queen Christina reached her majority, to help reform the Swedish education system. Comenius met the queen when she was sixteen, speaking in Latin, which she had learnt from Comenius’s textbooks.

![]()

But rather than moving to Sweden, Comenius settled with his family in Elbląg on the Baltic Sea, remaining there for the next six years. While engaged in this project, Comenius was actively engaged in his irenic activities, being harshly reprimanded by his Swedish employers for doing so. Specifically, he attended the Colloquy at Thorn or Toruń in Poland, searching for a common ground among Protestants and Catholics. To no avail. The participants could not even agree on the opening prayer.

Comenius’s attendance at this Colloquy also opened up suspicions among the religious bigots in Sweden, one of whom thought that his “pansophic scheme was nothing else but a cleverly disguised crypto-Calvinistic propaganda”. Although Comenius had the tacit support of the queen for his irenic, pansophic vision, he regarded himself as an ecumenical Hussite, able to stand outside himself. Once Comenius had published the schoolbooks required by his contract, he moved with his family back to Leszlo.

This was 1648, when the Thirty Years’ War came to an end with the Treaty of Westphalia, the final blow to Comenius’s deep longing for the return of the Czech Brethren to their native land. For this was expressly forbidden in the treaty; Bohemia and Moravia were to be solely Catholic, with no Protestants allowed to live there. As Comenius realized, this was the death-knell for the Unity of Brethren, Comenius being the final bishop, elected as its senior at about this time.

In this capacity, he felt the need to visit a settlement of Moravian Brethren in Hungary, under the protection of the Calvinist princes of Transylvania since 1628. Then, coincidentally, in 1650, he received an official invitation from Prince Sigismund, clearly encouraged by his redoubtable mother Susanna Lorántffy, the dowager princess, to attend a conference concerned with school reform and the pansophic project. Upon arrival, he discovered that the prince, his brother George, and their mother wished him to settle in Hungary, to put his theories into practice in one particular school at Sárospatak.

Eventually, after some hesitation, Comenius acquiesced, only to find much opposition from the rector of the school. Comenius held that education should be pupil-centred, with the subject matter made as interesting and dramatic as possible, involving the active participation of the learners themselves. As he ruefully said to Princess Susanna, “My whole method aims at changing the school drudgery into a play and enjoyment. That nobody here wishes to understand.” Nevertheless, she persuaded him to remain in Hungary for four years, despite all the difficulties.

While there, Comenius wrote Orbis Sensualis Pictus (The World of the Senses in Pictures), an illustrated children’s book, the first of its kind in the world, the most popular textbook in Europe for a century or more, being published in the USA to much acclaim in 1887. Orbis Pictus was originally published in German and Latin in 1658, translated into English the following year with the subtitle A World of Things Obvious to the Senses drawn in Pictures.

The book contains over 150 engravings, covering every aspect of human experience, depicting not only familiar forms, such as animals and the human body, and occupations, such as fishing and bread making, but also abstract moral concepts like patience and diligence. There are even pictures of the human soul and of God, as “A Light inaccessible; and yet all in all”, a depiction of the Coherent Light of Consciousness. This is an utterly amazing book, which I only discovered in August 2017.

The book contains over 150 engravings, covering every aspect of human experience, depicting not only familiar forms, such as animals and the human body, and occupations, such as fishing and bread making, but also abstract moral concepts like patience and diligence. There are even pictures of the human soul and of God, as “A Light inaccessible; and yet all in all”, a depiction of the Coherent Light of Consciousness. This is an utterly amazing book, which I only discovered in August 2017.

![]()

After Comenius’s return to Leszlo, disaster struck once again in 1656, when Catholic Poles broke into the city, burning a thousand houses to the ground, destroying Comenius’s library and practically all his unpublished writings. After this great calamity, he moved to Amsterdam to be among friends, who arranged to publish all his pedagogical writings as Opera Didactica Omnia in four volumes, covering the four major periods in his life.

He settled down to devote all his spare time to his long-awaited pansophic writings, the most important of which was his magnum opus titled De rerum humanarum emendatione consultationis catholica, (A Holistic Consultation Concerning the Improvement of Human Affairs), catholica meaning ‘relating to the Whole’. Consultation was to consist of seven parts, which Comenius began to write in 1644, titled Panegersia: ‘Universal Awakening’, Panaugia: ‘Universal Light or Dawning’, Pansophia: ‘Universal Wisdom’, Pampædia: ‘Universal Education’, Panglottia: ‘Universal Language’, Panorthosia: ‘Universal Reform’, and Pannuthesia: ‘Universal Admonition or Warning’.

In the event, only the first two parts were published, in 1656, and it was long thought that the others were lost. However, in 1935, Dmitry Chyzhevsky found the others in the library of the Orphanage of Halle, where they had been deposited by Daniel, Comenius’s son, and his associates Christian Nigrin and Paul Hartmann. What has survived of Consultation has been available to scholars in its Latin version only since 1966. Then in the 1980s and 90s, A. M. O. Dobbie translated all these works into English, but it is not easy to find them even in libraries and Pansophia is nowhere to be seen in the catalogues.

Despite his great acclaim throughout Europe, when Comenius died in Amsterdam in 1670 at the age of seventy-eight, he was disappointed that his lifelong effort on behalf of ecumenical Christendom and of his pansophic vision had not come to fruition. As he was to ruefully reflect in his old age, “So far almost nothing has been accomplished, but perhaps my labours shall succeed yet. Nothing has been accomplished because of the stubborn irreconcilability of some men to whose implacable animosity my friends did not deem it wise that I should expose myself.”

But is the world today any different from the 1600s, at end of the Humanistic Renaissance, in the middle of the first great revolution in science, and at the birth of the Ages of Reason and so-called Enlightenment? Yes, there are many awakening individuals and institutions working outside academia and the organized religions to realize something along the lines of Comenius’s vision.

However, in general they are still operating within the scientific and commercial framework of the dysfunctional Western civilization. Hence the urgent need to establish the Alliance for Mystical Pragmatics, as a school for autodidacts, at least, returning Home to the Nonmanifest, if this is meant to happen before our inevitable demise as a biological species.